Global study reveals key differences that explains vulnerability to infections and chronic illness

Why do some people frequently catch cold, while others are prone to bone diseases? An international research team inches closer to finding why our susceptibility to disease varies.

They have discovered that the composition of specific human immune cells, which are shaped by genes, sex, age and pathogens, diverges significantly across populations in five Asian countries1.

“The outcome of this knowledge is the first Asian Immune Diversity Atlas (AIDA) that aims to answer what causes Asian populations to be predisposed to certain diseases,” says co-author and geneticist, Arindam Maitra, at the National Institute of Biomedical Genomics in Kalyani, West Bengal.

The data, Maitra adds, could potentially be used as a healthy reference immune data for describing disease-mediated alterations with an emphasis on inflammatory, blood-borne and autoimmune diseases, and for developing novel therapies.

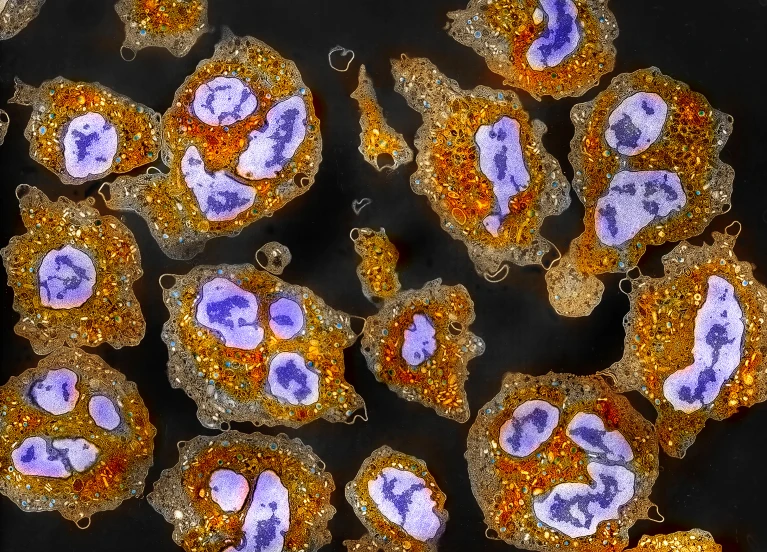

Human immune system consists of innate and adaptive immune cells that include white blood cells. Natural killer (NK) cells, macrophage, neutrophils and dendritic cells are innate immune cells that attack any pathogen. B and T cells are adaptive immune cells. B cells produce and secrete antibodies which bind to pathogens or toxins and neutralise them. T cells can wipe out infected or cancer cells.

Previous genomic studies have focused on European populations, leaving a gap in understanding the diversity of immune cells in Asian people. The researchers analysed 1.2 million peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), immune cells with a single, round nucleus, from 619 healthy donors from India, Japan, South Korea, and Thailand, including Indian, Chinese, and Malay living in Singapore. They also sequenced the genes of single immune cell.

The team, which included researchers from Singapore, Japan, Thailand, Italy and the United States, detected that Indian people have lower NK cells, but higher naïve B cells. NK cells destroy infected and cancer cells. Naïve B cells, which differentiate into antibody-producing plasma cells or memory B cells, recognize specific antigens (toxins or microbes).

“We don’t know the exact reason for such an effect in Indians,” says co-author and geneticist, Partha P. Majumder at the John C. Martin Centre for Liver Research and Innovations in Kolkata, who led the researchers in India. “However, it is possible that India has higher prevalence of certain primary immunodeficiencies and some autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.”

B cells were more abundant in women, while NK cells were more common in men, indicating a clear sex-specific difference. Specific T and dendritic cells were found to decline with age, affecting immune responses in older people.

Naive B cells are relatively more scarce in males than in females. This gender-specific difference in naive B cell proportion was the highest for Indians living in Singapore. Indian males living in Singapore have fewer naïve B cells than those in India. “This will help understand how environment, lifestyle, and diet change the immune landscape in two groups of people who are living apart but descended from same ancestral population,” says Maitra.

The researchers also zeroed in on expression quantitative trait loci — genetic variants that affect gene expression in specific immune cells. Many gene variants that are unique to Asians are rare or absent in Europeans. A variant in the FCER1A gene, linked to allergy susceptibility, was found at higher frequencies among Indian people.

Matteo Iannacone, an immunologist at the San Raffaele Scientific Institute & University, in Italy, says, “AIDA could potentially aid cancer immunotherapy since it highlights population, and sex-specific differences in subsets of T cells and NK cells.”

“It also shows that variants affecting immune gene regulation in one population may be entirely absent or functionally irrelevant in another, which explains why disease risks — and responses to treatments — may vary dramatically,” notes Iannacone.

The researchers say PBMCs express more than 80% genes of the human genome and these cells can act as markers of immune-related diseases. “These immune cells are most important for different infectious diseases like TB, dengue, and kala-azar,” Majumder points out. Specific immune cell types and cell states are affected in certain diseases — macrophages are affected in TB infection, CD4+ T cells in HIV, and platelets in dengue, he adds.

Immunologist Nimesh Gupta at the National Institute of Immunology in New Delhi, not associated with the AIDA team, says further research is needed to identify biomarkers or develop therapies for tropical diseases like TB, kala-azar, dengue, or malaria. “We require disease-targeted studies that incorporate single-cell analyses focused on pathogen-specific immune signatures,” he adds.